Why I May Vote for Obama This Time. If I Vote.

I’m awfully tempted not to. Sickened by the ever stronger resemblance of partisan politics to football, where getting the ball away from the other team and into one’s own end zone has become an end in itself, and the presidential election is the Super Bowl. Nauseated by the prioritization of winning and spoils over governance, the frosting of self-righteous ideology over self-interest. (Everybody loves big government if it enables their class, from Wall Street to welfare. Wallfare.) Gagged by the subscription to prefab sets of ideas that are shibboleths for membership in one or the other group of We Are the Good, the Better Sort. Bewildered by the crude misfit of polarized ideas to reality, which always seems to me to be neither/nor and both/and: Poverty’s the poor’s fault/poverty’s the rich’s fault. Abortion is a sacred right/abortion is a heinous crime. Well, yes and no. (As I tried hard to express here, but of course it is inexpressible. That’s why Taoists shut up, or talk nonsense.)

But I have a friend who used to be a diplomat in communist Eastern Europe, and he once said to me, “You have to vote. Because you can.” Every time I consider not voting, I hear him say that.

As a voter, the main principle guiding me seems to be countersuggestibility. I’m not sure some of my family and friends even know that I didn’t vote for Obama last time. I didn’t have the courage to tell them, because I frankly thought some of them might stop speaking to me — that’s how tribal politics has become. But also, not voting for Obama was not some grand declaration of principle or ideology. I simply didn’t think he was qualified for the presidency in terms of executive experience, and I thought that if I wouldn’t vote for a white guy with the exact same bona fides, voting for Obama just because he’s black would be racist. That left me, I thought, with no unquixotic choice but to vote for McCain, who was too old (if there was ever a time for him, it would have been 2000) and possibly a loose cannon. But I wasn’t afraid of conservatives per se (other friends of mine, who may now stop speaking to me, are), and I respected survivors.

I expect Romney will win in November — we always change presidents when the economy’s bad, and it is still awful — and I’m not afraid of him, either. In every way (including the Brylcreem) he seems like a throwback to the Nixon era, a pragmatist and a manager, not an ideologue. All his flip-flopping just says to me that he’s a political opportunist who will put on the cloak of whatever ideology will get him elected, and then throw it off and get to work, with fairly nonideological results. (Exhibit 1: Massachusetts.) I’m not afraid of his Mormonism, either. Such Mormons as I know seem to pretty much ignore their screwy theology and concentrate on clean living and efficiency.

So why vote for Obama, who has been a predictably weak president in many respects (though a stronger one on national security, of all things, than one would have expected)? Because I can’t stand his automatic demonization any more than I could his automatic deification. Conservatives’ visceral hatred and distrust of him seems as reflexive and a priori as liberals’ reverence for him. It’s like the Zen koan “Show me your original face that you had before your mother and father were born.” Conservatives hated and liberals loved Obama before he was born.

I might vote for Obama for the same reason I didn’t vote for him before: because he’s just a guy. He wasn’t the savior, and he’s not the devil. How perverse is that?

My favorite presidential candidate was the unesthetic, no-bullshit Chris Christie, a Republican who dared to say human-caused global warming is real. (Not that I agree with him; I admire him for breaking ranks.) If he were Romney’s vice-presidential choice, it might sway me. But he won’t be. Romney’s choice will be someone more telegenic and demographic, like Rubio. Besides, Romney is probably healthier than Christie, and you want it to be the other way around.

*Sigh* Okay, bring it on.

Dogcows and Chickens, Cont’d.

Isn’t he magnificent?! This is mockturtle’s rooster, Mac.

Now mt and Karen can tell us what breed of chickens this is and what’s so special about them, and fifteen comments down heaven only knows what we’ll be talking about!

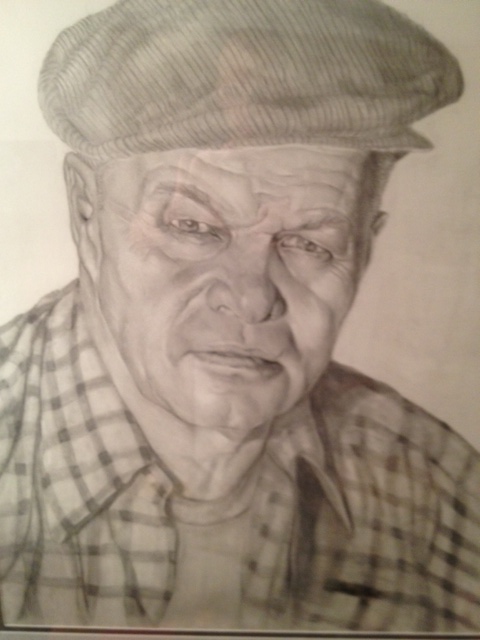

J’s Awesome Portrait

by our longtime friend Albert Mitchell.

(It is framed, and the photographer’s reflection in the glass accounts for the slight discoloration of what is a silvery-toned pencil drawing.) Made in 2000 from a photograph, J’s 1980-or-so acting headshot, the drawing captures much more of J’s life than the photo did. Albie knew him. When I hung this picture above J’s ashes, I felt as if I had reunited his matter and spirit for the first time since they went their separate ways.

iPhone Abstainer

To the tune of “Daydream Believer”?

As I contemplate giving in and getting an iPhone, thus joining the rest of the planet in being perpetually networked, located, and informed, a deliberate contrary resolve NOT to do so is growing stronger.

The pros and cons:

PRO

If I’m on unfamiliar turf and suddenly remember that I need something from a Walmart or a Walgreen’s or a PetSmart, I can find one nearby. (Presently, I have to save it for a separate trip.)

If I get lost I can get found again quickly—particularly helpful to one who tends to allow barely enough time to get to appointments.

The camera. I can document my life and observations like a good blogger. I am not an image person, but describing things, like sketching things, takes time and energy. A snapshot may not be worth a thousand words, but it is a thousand times faster than a thousand words.

Google, for conversation enhancement and curiosity feeding. At home, I’ll run to the computer and look something up just for the hell of it. I could see taking that functionality portable.

CON

(Note that some of my cons are precisely the things that other people would consider pros, and are even the flip side of my own pros.)

I do not want to be available to e-mail, Facebook, etc. all the time. (I’m addicted enough as it is.)

I don’t want to be staring at a screen any more than I already do. My eyes are forgetting how to focus beyond two feet away.

I do not want to have music, pictures, and the Internet available to me while riding the train, walking on the street, or waiting in line. I want to be forced to look at and eavesdrop on my fellow humans (so I can get depressed by how many of them are hunched over their iPhones or iPads or umbilically swaddled in their iPods). If I really can’t stand it, I’ll carry something to read. (For the preceding reason, probably NOT a Kindle.)

I like getting lost. Some of my best adventures and discoveries happen by getting lost. (You’d think I’d love having my own GPS because, like a stereotypical guy, I tend to stubbornly avoid asking for directions. And I’ll use a map. So why not an iPhone? Because it is one of those sense-imprisoning, sense-dulling electronic devices that take us out of the freshness of the real world and into this glazed-in, stale, stuffy perpetual airport that is the virtual world. Lemme out!!)

I like looking at things better than I like taking pictures of them, especially because getting the picture often jostles aside looking and seeing. (I didn’t get a picture of the new WTC, but “in the silver light of a rainy summer evening, it had a swooping curve like one of those mermaid Mae West dresses that nip in at the ankles, only leaner and sharper; and it had a string of starry construction lights for buttons. The bumps on my skin tingled and twinkled like stars in response. The growing shaft, silver as the silver sky, plunged stilly up out of the earth with that vaunting, rocketlike defiance that makes skyscrapers take your breath away.”)

I don’t know yet which impulse will win. The contrarian impulse may prove to be too quixotic, isolating (with no TV and no steady companion[s] I’m already living on the moon), and just plain inconvenient. I would feel like a sort of retro-pioneer, prowling a deserted antediluvian frontier where a few living fossils still find their way by deploying their senses in three-dimensional space, and obtain information by exploring or asking somebody.

All By Myself

Slept late; sat here in a daze of relief all day, working on and off, hardly moving because the kitten (spayed yesterday, that violent word like a sharp tool) is all right. Close to 7 I remembered with a start that I had a ticket to a theatre production somewhere downtown at 8. It was a preview of this, which is based on one of my all-time favorite books. I keep giving the book to people but no one seems to love it as much as I do (ever notice how often our impassioned gifts of the food, books, or clothing we love fall flat with the recipient, and vice versa? Taste is induplicable), so I went by myself, dressed up in my half-assed way. Nobody cares but me, and there’s a freedom in it.

It was at Rector and Greenwich Streets, way downtown. I never did know downtown well and I know it even less now, so I tried to Google a subway route. Google Maps was way wrong. Turns out the number 1 Broadway line train from Sheridan Square would have taken me straight to the doorstep, but Google Maps didn’t have a clue of that. It told me I had to come upstairs at World Trade Center and go back underground around the corner at Fulton Street.

And so it was that I came up out of the subway right in front of the growing shaft of the new World Trade Center building. Faster than I could react consciously, I got goosebumps. It doesn’t look like all that much from a distance, so it caught me off guard that close up it was so awesome, silver against a silver sky. I can’t find a picture that looks the way it looked. Just one more reason to break down and get a fucking iPhone. (Or is it? If I’d had an iPhone I wouldn’t have gotten lost, wouldn’t have been startled by the building close up, wouldn’t have walked by the worn-thin gravestones in Trinity Churchyard and felt bracketed by the extremes of American history, wouldn’t have had to ask surprised strangers for directions. It seems to have happened in the blink of an eye: no one looks at anyone anymore, no one gets lost and has to find their way using only their senses.)

I don’t know if the play would have made sense to someone who didn’t know the book as well as I do, but I sat breathless on the edge of my seat and, at certain key moments, cried. The emphasis on dreams, which I need to reconnect with, and the director’s essay in the program, full of Taoist ideas about the virtue of uncertainty, told me I was where I belonged. It was mostly beautifully done, with scrims and large-scale video projection that transformed the simple set into a dreamscape — much truer to the book than the PBS film adaptation released in 1980. It could have been even better. Afterwards I found the adapter/director at the door and thanked him, told him the one scene I wished he had done more with, and how one of the actors needs to speak up. I didn’t go on and on, but his eyes looked for escape; it was a busy moment for him, and I am neither young and beautiful nor old and important, so nobody cares what I have to say. And I don’t care that they don’t care. I’ll say it anyway, or not. It doesn’t matter.

There’s an absurd freedom in not mattering at all, wandering like a neutrino (the particle that interacts with nothing at all, but passes right through matter) through an island of 5 million striving, connected people. I have a feeling that later on, when my life is more mundane and perhaps more structured and companioned, I’ll be nostalgic for this.

Perseverance Isn’t Everything, It’s the Only Thing.

(Pace Vince Lombardi.) This is a big theme with me. It’s the central tenet of my worldwide karate school, whose all-purpose salutation, OSU! (used rather like “Shalom” to mean hello, goodbye, I hear you, I understand, I’ll try hard), is a contraction of Oshi shinobu, “endure under pressure.” It was the epiphany I had from reading the incredible story of the Hubble Space Telescope (I highly recommend this book) . It is the biggest lesson experience—of not persevering, at least as much as of persevering—has taught me.

But what I want to share with you right now is a very small, seemingly trivial example. A puzzle.

An acrostic puzzle, in last Sunday’s New York Times Magazine, that I worried at like a tenacious terrier all day. I’m usually pretty good at these puzzles, in which crossword-type clues below provide letters to fill into numbered spaces in a passage from a book, above. The initial letters of the solved clues below will spell out the names of the author and the work. As you begin to spot the shapes of words and sentences in the passage and to fill in missing letters, these in turn help to fill in the answers to the clues below. It’s an enjoyable interplay between two kinds of guesswork—solving clues and seeing word-and-meaning gestalts—and I’m much better at the second kind. Often I’ll be able to solve only a few of the clues, but putting just a scattering of letters into the passage may enable me to begin to see what it says. (This is the same autistic-savant talent that once won me a car on Wheel of Fortune.)

So yesterday, when I tackled last Sunday’s puzzle, which my dad had saved for me with one clue filled in, it was an affront to my amour-propre and a challenge to my chops. First of all—no fair!—the answers to three of the clues below (J., “First name of this quote’s author;” Q., “With R., author who wrote about J.”; R., “See Q.”) seemed to depend on having already solved the passage. (It was even worse, and better, than that.) Then, as the passage began to take shape, it didn’t make any sense. OK, that looked like “Young people” at the beginning, but “Young people at the most”? “Young people on the moor”? These young people had something—did it really say “thirty books”?—”in their pouches,” or maybe “in their pockets, or hanging on the pommels of their saddles.” Huh? “Attached books to my ears as pendants”—books? Can’t be. Even more confusingly, as more clues came clear, the “author” of the passage seemed to be a fictional character, Cyrano (J.) de Bergerac, written about, of course, by Edmond (Q.) Rostand (R.). This puzzle was breaking all the rules!

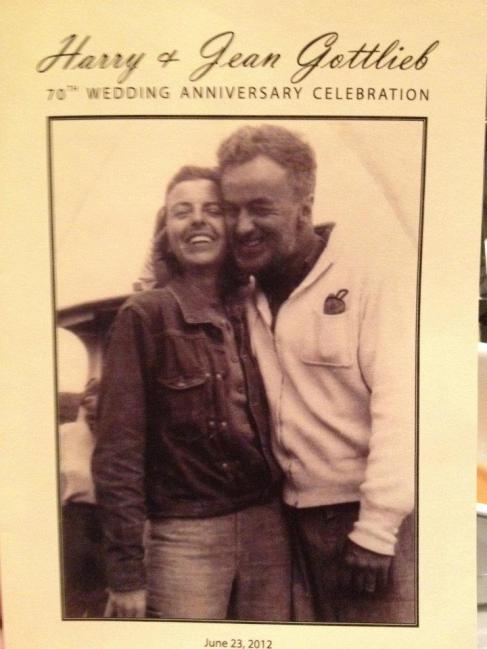

I kept hitting a wall, putting it aside, doing some work, listening to my parents’ delightful anniversary reminiscences about what they were doing on and around their wedding day 70 years ago, and then coming back to the damn puzzle. I couldn’t leave it alone. It was a matter of pride, but far more, a matter of dogged, ornery curiosity. What the hell? Finally, this was it—and it still didn’t make any sense:

Young people of the moon can have thirty books in their pockets or hanging on the pommels of their saddles. They need only wind a spring to hear one. I attached books to my ears as pendants and went for a walk in town.

~ de Bergerac, The Other World

Weirdest of all was that it seemed to be a description of an iPod, as sported by a lunar gaucho, or ???

The payoff for my perseverance (in my experience, it always rewards!) came when I Googled this enigma. Who knew there was a real Cyrano de Bergerac, on whom the fictional lovestruck swordsman was loosely based—a fierce enthusiast of nascent science, a founder of the genre of science fiction? And that, in a book “historically referred to as Voyage dans la lune, ‘A Trip to the Moon,’” but which Cyrano insisted on titling L’Autre Monde ou les états et empires de la lune—a book written in 1650—Cyrano, like Leonardo, had imagined inventions that wouldn’t exist for 350 years? Books attached to my ears as pendants?!

And here is the whole book! And here is a succinct tribute to Cyrano’s “revolutionary spirit.” And here (breaking my usual rule) is a pretty good biography on Wikipedia, in which we learn that Cyrano influenced Jonathan Swift.

Moral of the story: if I had given up on that puzzle, I would never have learned any of this.

I, Weed.

Unknown and therefore unchecked by public opinion, without any ‘stake in the country’ and therefore reckless . . .

That’s how the English anti-Semitic writer Henry Wickham Steed explained the “unfair advantage over the natural-born Viennese” that enabled the successful Jewish businessman or financier, arrived from Galicia within a generation or two, “to prey upon a public and a political world totally unfit for defence against or competition with him.” This is from The Hare with Amber Eyes, a page-turner of a memoir by a descendant of one of those Jewish banking families, who follows the fortunes of a collection of Japanese netsuke he’s inherited to trace his family’s rise and fall in, seeming assimilation into and convulsive expulsion from, Parisian and Viennese society in the 19th and 20th centuries. (Yes—I’m actually finding the time to read a book!!)

Why do I quote this? Because, having been immersed in ecology and natural history lately, I recognized, with a start, pretty much the exact same language that ecologists use to deplore and traduce invasive, opportunistic species.

Not having coevolved with the rest of an ecosystem, these species have no natural constraints on their growth, such as predators, and no “stake in the country”—no dependence on the evolved, stable balance of the ecosystem. Similarly, the Jews who fled Galician pogroms for the cities of Central and Western Europe in the 19th century didn’t “know their place” because they had no place, and this enabled some to be immensely successful. Like invasive plants they thrived and found new niches in soils disturbed by change, and they accelerated change. With invasive plants and animals, ecologists—like the “blood and soil” defenders of Europe’s settled, traditional order—try to restore the status quo ante of an ecosystem by programs of exclusion, confinement, and if that doesn’t work, eradication.

Does this analogy make me feel more sympathy for the defenders of tradition? No, as a Jew—an opportunistic weed myself—it makes me feel more sympathy for kudzu.

The analogy is hardly perfect. Invasive plants, marine organisms, goats, rats, or cats can really overrun an ecosystem, outcompeting or just plain eating unique endemic species ill equipped to adapt. A small minority of Jews can hardly be said to have done the same to Western European civilization—which, if anything, they enthusiastically adopted and arguably revitalized—though it is sobering to realize that that’s exactly how the “blood and soil” nativists saw the financial success and cultural ubiquity of a minority of the minority.

But it should make us question the impulse to try to restore ecosystems or societies to the way they were. Biodiversity is an irreplaceable trove of genetic creativity, but nature itself is quite heartless toward it. Nature’s one constant is change, even though it goes in pulses that our lives are sometimes too short to perceive, and change is never all good or all bad; it destroys as it creates. For further examples, we need look no further than the arrival of Europeans in North America . . . or the emergence of an upstart, upright species out of Africa.

Lagniappe

n [AmerF, fr. AmerSp la ñapa the lagniappe, fr. la + ñapa, yapa, fr. Quechua yapa something added] (1844) : a small gift given a customer by a merchant at the time of a purchase; broadly : something given or obtained gratuitously or by way of good measure

~ Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th Edition. Kindle Edition.

It’s a word readily traceable to the New Orleans area. Quechua, though?? They’re in Peru. How the heck . . . ? If that word could talk . . .

It’s always sounded to me like cream, with a cat lapping it.

It occurred to me just now as a word for this time of my life. Others are optional, light, superfluous, unnecessary. For almost four decades I lived with and was necessary to someone rooted in necessity. After an upper-middle-class American upbringing, I appreciated the way that staked me down and sorted me out. I was never very good at, or very interested in, luxury or frivolity or even fun. Not that I was Puritanically averse to them, they just seemed like a very small and dispensable part of life. (By “fun” I do not mean “humor,” by the way. Humor and necessity share a bloodstream.)

But this part of my life is sheer luxury. It really doesn’t matter what I do with it. There’s great freedom in that, but also absurdity. It’s up to me, at my discretion, to fill this free gift of time. I could rush out and find more necessity to submit myself to (become a nanny to a small child, or a hospice volunteer), but right now I have a strong sense of been there, done that. If it puts itself in my way, that’s something else (I do intend to use my Feldenkrais Method training to design a workshop for caregivers), but seeking it out seems almost like a panicky cop-out from braving another mode and beat of living. I’ve had trouble getting a handle on it.

Somehow, the word lagniappe helps.