An important and scathing article

about doing politics vs. just talking about it. Point taken. Shut up and deal.

In reality, political hobbyists have harmed American democracy and would do better by redirecting their political energy toward serving the material and emotional needs of their neighbors. . . .

[C]ollege-educated people, especially college-educated white people, do politics as hobbyists because they can. On the political left, they may say they fear President Donald Trump. They may lament polarization. But they are pretty comfortable with the status quo. . . .

Our . . . treatment of politics as a sport incentivizes politicians to behave badly. We reward them with attention and money for any red meat they throw us…Rather than practic[e] patience and empathy [as organizers must], hobbyists cultivate outrage & seek instant gratification. . . .

[The Democratic Party harbors] “a tension between those who…seek empowerment and those who have enough power that politics is more about self-gratification than fighting for anything. Only if you don’t need more power . . . could you possibly consider politics a form of consumption from the couch.”

Of course many of us political couch potatoes are riveted to the news not for entertainment and outrage, but out of anxiety. But the remedy for anxiety is action—on behalf of the people we purport to care about who will be hurt worse than us.

A rant about the phrase “most Americans”

is live on The Compulsive Copyeditor:

“A new CNN poll shows that most Americans want the Senate to remove Trump from office (51 to 45 percent), most want to hear from the witnesses that Trump blocked from testifying in the House (69 percent), and most believe that he abused the power of the presidency (58 percent) and obstructed Congress (57 percent).”

~ Teresa Hanafin, “Fast Forward” (Boston Globe newsletter)

I’m sorry, but no matter where you stand on Trump, the Senate, impeachment, or CNN, 51 percent is NOT “MOST” Americans. It is, for all practical purposes, half.

Strange tree dream

A grove of tree trunks is standing deathly silent and still in a dim, shadowy place that is somehow indoors. I don’t see beyond the trunks, but the feeling is undergroundish, like a parking garage or deserted warehouse. The trunks are close together, and the darkness thickens between them. They’re a deep brown, very straight like pillars, more than twice as thick as my arms would go around, with regular, vertically grooved bark. Thinking of it now they could be redwoods, but in the dream I thought of them as elms.

My brother is with me and I’m calling a report back to him. I find myself climbing one, or find that I have climbed it. At first I thought of grasping the grooves, but it’s easy to shinny straight up because the bark is almost sticky, not in an icky way but in a pleasant, textured way, like rough fabric (burlap? corduroy?) with a rubbery coating, conferring on me the sense of having sticky pads for fingers like a lizard. It welcomes climbing; it has a gravity-canceling effect, so that climbing is almost effortless and feels safe.

But before I can climb up into any spreading branches, I am stopped. The upper part of the tree has been sealed off by a badly made cement (concrete?) ceiling that closes in tightly around the trunk. I can see cracks and nails and corners in it, it’s not form-fitting—made with brutal indifference—but no light or air or sight can squeak through. And it’s certain that as the tree continues to grow the cement will press into it.

Above this ceiling branches must still spread and wave, there must be leaves to feed each tree and air and sky, but all that is sealed off from the trunks. It’s been done with the assumption that trees don’t “know” or “care,” but how could they not?

Other than having been surprised to read in the course of work that robust sequoias are dying, and that there are elms in coastal wetland forests being inundated by salt water from sea level rise—they were the trees of my childhood street and I thought they’d all been killed long ago by dutch elm disease—I have no associations to this and no idea what it “means.” But it feels like life now, public and private, they can’t be separated.

UPDATE: Speaking of trees, Republicans want to plant trillions of them. See, says House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy, “we care.” In the words of one of his colleagues from Arkansas, “Trees are the ultimate carbon sequestration.”

I wrote about gender and 2020

The picture is chaotic and infuriating, ruled by a nasty mix of timidity and calculation. Progressives think a centrist is not electable; centrists think a progressive is not electable. Significant numbers of each group seem prepared to make their prophecy self-fulfilling by staying home or casting a protest vote if a candidate from the other group wins the nomination. Many women who say they would welcome a female president are so sure that the majority of their fellow Americans wouldn’t that they are hedging their bets by supporting a (white) man. . . .

(Whether or not Bernie Sanders [shares that view] I will leave to your speculation. I am quite sure he believes a woman would be capable of serving as president. I am not so sure he is immune to the widespread worry that America is not capable of electing one. But that’s a subtle distinction long since trampled by the wildebeests of propaganda.)

Amazing Stuff 3

These undersea photos are past amazing, they’re astounding—for the beauty and strangeness of the creatures, for the technical brilliance of the photographs and the excruciating patience it must have taken to get them, and in a sadder way, for the evidence of our impact in every part of the ocean—the plastics that creatures cannot avoid breathing or swallowing, the strangling nets. Photographers no longer seek out the illusion of “untouched” nature. We’re forced to admit there is no such thing.

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil; And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell . . . ~ Gerard Manley Hopkins, “God’s Grandeur” (1877)

The rain bore a brand; it was a steer, not a deer. And that was where the loneliness came from. There’s nothing there except us. There’s no such thing as nature anymore. ~ Bill McKibben, The End of Nature (1989)

√

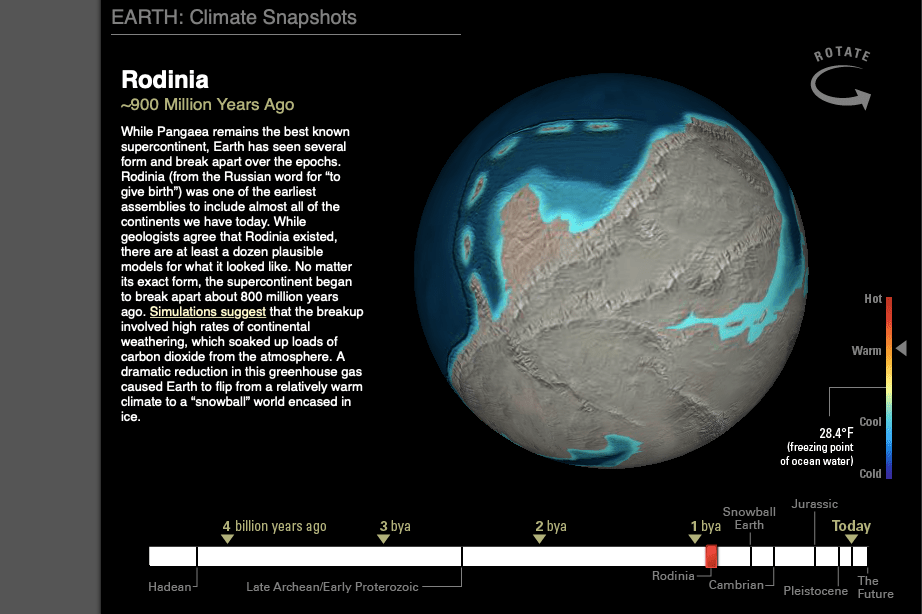

INTERACTIVE: EARTH OVER TIME

Smithsonian Magazine lets you scroll through the eons.

We once had orange skies and bright-green or blood-red waters, says Ferris Jabr, exploring the evolution of Earth’s palette.

√

The Ultimate Emotional Support Animal . . .

. . . if you consider the trope, “How do porcupines make love?” “Very carefully.”

√

√

Where the census begins, and why.

Alexander Hamilton’s Prophecy

He foresaw our moment with chilling precision. Ticked off every particular.

When I flagged only one questionable item—”having the advantage of military habits”—my brother said, “Well, he did go to military school.”

The view from 5 a.m.

Particularly since we lost our moorings in nature, we’re carried along in the torrent of human culture, trying to make a little mark, pitch a small shelter in the midst of this moving mass. But there is no fixed point of reference, the coordinates are constantly changing, driven now mainly by commerce, propaganda, psychopathology, and technology, and the directionless ferocity of trends. There is no way for an individual mind to get any purchase. And now this mass is accelerating like the Niagara above the falls. What do we do while we’re carried along toward the precipice? Our past plans have been pulled apart multiple times by the dissolution of their context, like a house frame in a flood.

Plans presuppose a world that holds still enough for long enough so their enactment still makes sense when it’s complete, if it can be completed at all. Interruption by crisis feels imminent: why commit yourself to a course of action that you’ll have to drop at any moment to simply survive? The universe wasn’t “absurd” until we made it so.

Is dematerialization and digitization, the dissolving of everything into a torrent of electrons, a response to this or a cause of it? Only a torrent is adapted to a torrent, only total fluidity and nonattachment can thrive. Momentary insights form and dissolve like snowflakes. If the material world once kept us anchored and sane, we’re dissolving that too, with the help of fire and flood . . . and finance.